Retracing Lewis and Clark and the Oregon Trail is a must for RVers.

With all the travel we’ve done, what has impressed us perhaps the most are the routes we took that touched parts of two historic routes: The Lewis and Clark Expedition and the Oregon Trail.

It’s hard to over-emphasize the importance of these two 19th century routes. Lewis and Clark discovered the overland route to the Pacific, thus opening up the nation to east-west travel in the days immediately after the Louisiana Purchase.

It was a trip that in its day, was as monumental as the American landing on the moon is to ours.

The Oregon Trail pioneers came four decades or so later in their prairie schooners. So named because their wagons were covered with white canvas that made them resemble a ship at sea.

Others took routes that sprang off the Oregon Trail on paths called the California Trail and the Mormon Trail as they headed to the Gold Rush and Salt lake City.

Retracing Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery Expedition

Retracing those routes in our RV – the modern equivalent of a covered wagon – was a stimulating journey. It all started with the wide Missouri River.

At 2,341 miles, the Missouri River is the longest river in North America. It is impressive to behold. But what you see today is much less than 19th-century explorers and pioneers encountered. We have messed it up through channelization and dam building, greatly changing the Missouri River.

Today, 67 percent of the Missouri is either channelized for navigation (650) miles or impounded by dams (903 miles). Most of the remaining free-flowing portions of the river are near the headwaters in Montana. Channelization has resulted in the lower river being about 50 percent narrower.

But like I said, it is still impressive. But realizing that it was bigger and wider and wilder 200 years ago makes you wonder how these early explorers did it.

The Big Muddy

Nicknamed the “Big Muddy,” the Missouri River has long been one of North America’s most important travel routes. Every bend in the river is saturated in history. Her waters saw the canoes of many American Indian tribes, fur trappers, explorers and pioneers.

The river served as the main route to the northwest for Lewis and Clark. Later, it became the primary pathway for the nation’s western expansion. The Missouri has witnessed the rise and fall of the steamboat era and given birth to countless communities that settled near her banks.

Confluence Point

We started our tour in St. Louis, where the Missouri dumps into the Mississippi at a place called Confluence Point.

Standing at the point where the nation’s mightiest two rivers merge, it’s hard not to think of all the dreams, all the hopes and aspirations that welled up in the hearts of those who came this way in the 1800s.

Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery took the Ohio River to the Mississippi, then the Mississippi to the Missouri. Thus began their official expedition of the west from this very spot in May of 1804.

Undaunted Courage

A great book that we to read is Robert Ambrose's Undaunted Courage. It's the definitive work on the expedition and fascinating reading.

I wish we had an audio version so it could play as we were driving. But it was unavailable when we ordered so we sometimes took turns reading aloud from the big paperback to each other as we were near the locations described in the book.

Arrow Rock, MO

A hundred miles west of St. Louis, we did our first overnight at a place called Arrow Rock, MO, a dozen or so miles north of I-70 near the Missouri River.

At this quiet, peaceful park, there's a monument overlooking a spot where, early on, Lewis and Clark faced their first of many dangers. Huge floating trees had toppled into the river when the Missouri currents undercut the banks they were growing on and threatened to smash their keelboat to bits.

The Arrow Rock State Historic Site here has a restored village and great camping. The campground is small, only 47 sites and fills up most weekends. We had no trouble getting in midweek.

The village of Arrow Rock was the traditional starting point for another historic trail – The Santa Fe Trail. In fact, as we move west, off the interstates and through the plains and into the Rockies, we saw several other trails all using parts of these same routes, the California Trail, the Mormon Trail, and the Pony Express Trail.

We found Arrow Rock a great place to read, research our route and, thanks to a great Visitor's Center, immerse ourselves in what life was like when, in the early 1800s, this was the last city on the western frontier.

Named because of a tall sandstone bluff on the Missouri that the Osage Indians used to chisel out flint for arrowheads, Arrow Rock once had 1,000 residents. Today, 56 live there.

In the summer, there's a professional theater – the Lyceum – that brings in tourists each day. We watched a production of Agatha Christie's Witness for the Prosecution and noted, as we returned to camp late that night, that many of our neighbors had also been at the play.

And the historic Huston Tavern, established in 1834, is the oldest continually serving restaurant west of the Mississippi. We found excellent, family-style food, especially the fried chicken, raspberry glazed ham, mashed potatoes, corn, biscuits, and cobblers to die for.

We liked Arrow Rock so much we stayed three nights, soaking up the landscape. We tried imagining what it must have been like for those pioneers so long ago who set off from the very place where we were parked beneath a cottonwood tree in our air-conditioned RV.

Not quite the same, to be sure.

Weston Bend State Park

We left Arrow Rock and continued west, past Kansas City, following the Missouri to the Weston Bend State Park near the town of Weston. Once a thriving river town but now – thanks to the river’s shifting banks – Weston is more of a trendy little place of antique shops and bed and breakfasts.

We overnighted at the Weston Bend State Park and watched the sunset at a Missouri River overlook where the Corps of Discovery set shore for some exploring .

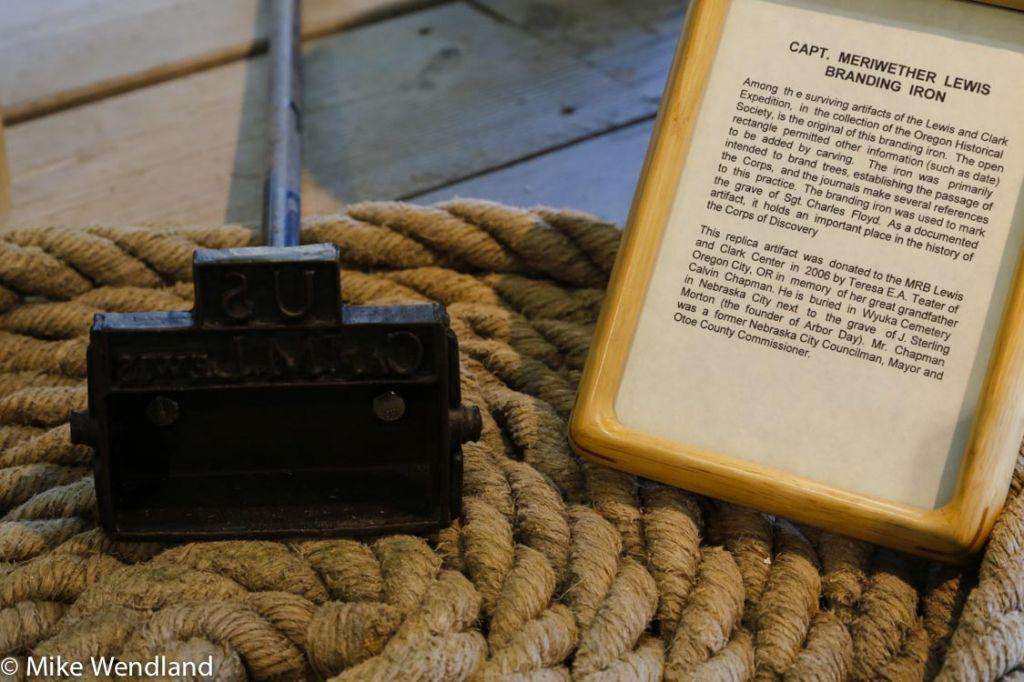

The next day it was north and west to Nebraska City, NE, and the Lewis and Clark Discovery Center on the river there. The center itself wasn’t much. Mostly some displays, including a branding iron owned by Lewis and used to emblazon trees along the route.

The thing that most interested me was a full-sized replica of the 55-foot long keelboat used by the expedition to navigate the Missouri. Originally made for a movie, it sits out front of the center and allows visitors to come aboard.

I grabbed one of the oars of the same type and size used by the crew and was amazed by how heavy it was and could only imagine what it would have been like pulling it hour upon hour against the currents.

There’s a shore trail that leads to yet another river overlook that made for a nice photo op. The river is still muddy and the current is obvious. The banks of the Missouri remain littered with snags and driftwood.

From Nebraska City, we took NE-2 west through rolling cornfields, slowly moving past the Missouri and closer to the Oregon Trail.

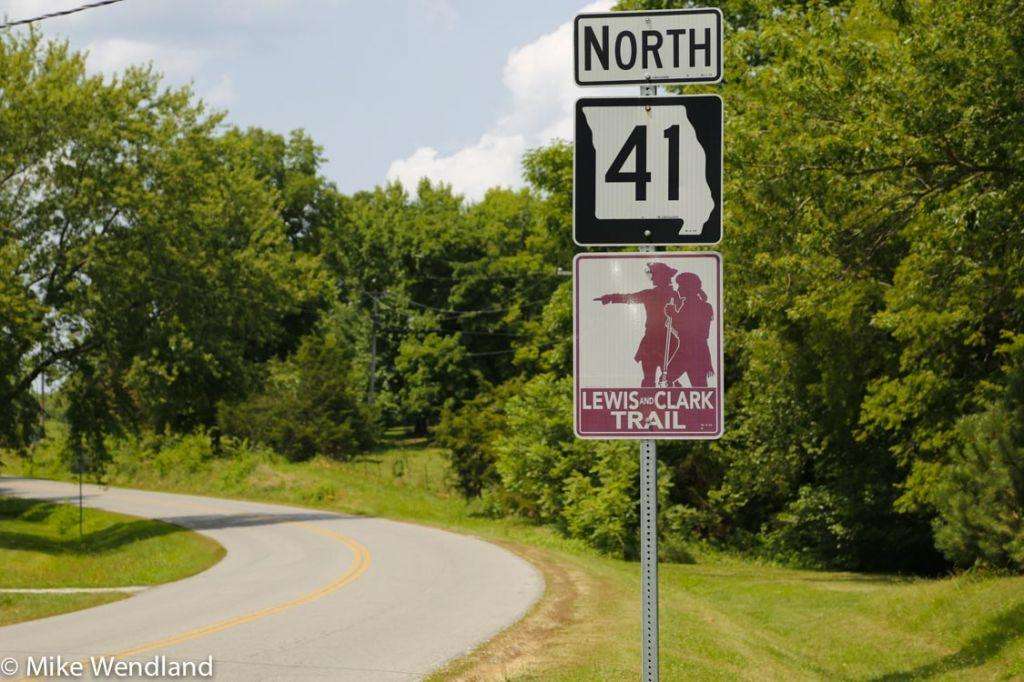

The nice thing about following these trails and the Lewis and Clary route is how well it's all documented for the traveler. Museums and historic markers make the route easy to find and follow – whether for a few days or the whole way to the Pacific.

The Oregon Trail

As we moved west, we picked up the Oregon Trail.

The Oregon Trail, and the ancillary trails that led from it, constituted the single greatest migration in America. As many as a half a million men, women and children traveled by wagon and by foot west for two decades in the mid-19th Century.

There are lots of books on the trail and lots of academic experts. But when it really comes to knowing the trail and experiencing it, there are few who can match Morris Carter.

Modern-Day Wagon Trail Excursions

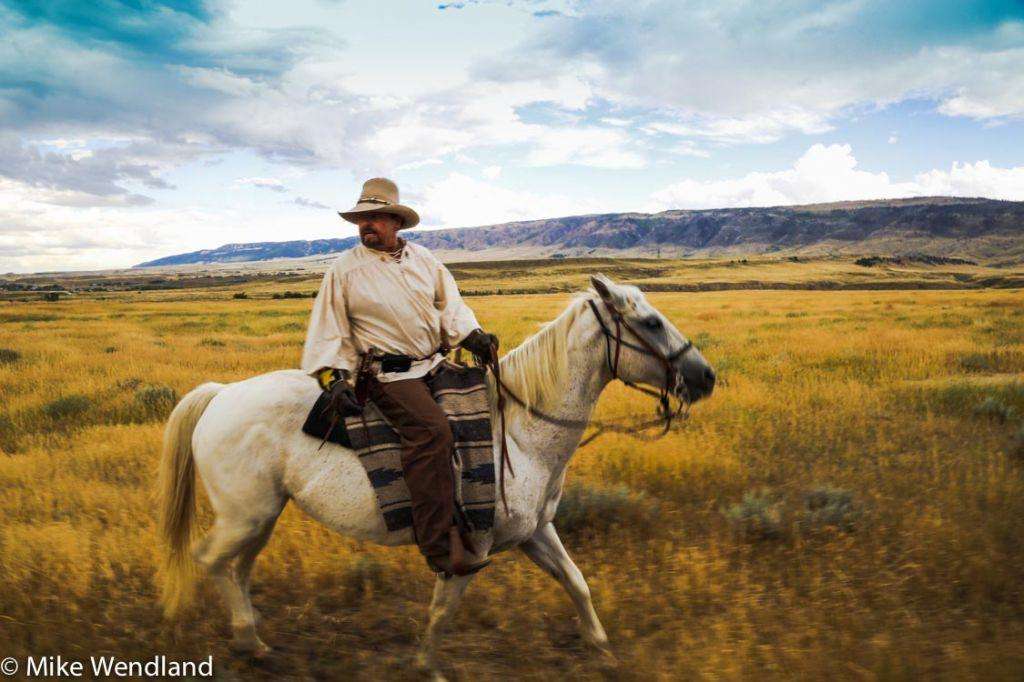

Morris Carter has built wagons that replicate those used by the pioneers. Plus, he’s actually made the 2,600-mile wagon train trip himself, from its start in Independence, MO to the final destination in Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

That 1993 trip was followed by a similar trip in 1999 along the 2,500 miles of the California Trail.

Others may have read the books and journals of those original pioneers, but Carter – who has also read them all – has done it. Really done it, in a wagon pulled by horse along the same routes used by those who settled the west.

And today, from his home in Casper, WY, he leads modern-day wagon trail excursions whose route literally parallels the still-visible ruts left by those who traveled the Oregon Trail 150 years ago.

His trips range from four hours to overnights and week-long trips. Those who travel with him stay overnight in Tee Pees, are fed Wyoming steak dinners around a campfire and regaled with Carter’s encyclopedic knowledge of what it was really like to make the trip, which typically took six months.

“There are a lot of misconceptions about the Oregon Trail,” Carter told me. “It wasn’t just one wagon most families took. It was two or three. They took everything they had to set up and furnish their new homes in the west. And the trail was usually crowded. The string of wagons often stretched out as far in front and in back as you could see. The wagons would be sometimes 10 across. They’d average two miles an hour when pulled by oxen, maybe four if by horses.”

Dangers of the Oregon Trail

As I walked alongside the wagon taking photos on one of his tours, he repeatedly warned me to watch for rattlesnakes. I didn’t see any. Thankfully. “They’re all over out here,” he said. “Fortunately, they’re watching for you, too.”

No wonder Jennifer decided to stay in the wagon.

In the original migration, most people walked, Carter said, making it easier on the animals. “Some walked the entire way,” he said. “Many were barefoot.”

The biggest danger was accidents. Falls off wagons, under wagons, being tramped or kicked by a horse, snakebite. Disease was widespread, especially cholera. There was a saying the pioneers had about the thousands who died from the virulent intestinal disease: “Healthy at breakfast, in the grave by noon.”

Indeed, as Jennifer and I have visited various spots along the Oregon Trail from Missouri westward, we have seen several grave sites of pioneers who died along the trail of the disease.

There were also Indian attacks. One wagon train was wiped out just a couple of miles from the route we traveled. That same band of Indians also killed an entire cavalry platoon sent out to protect the ill-fated wagon train.

Our Experience on the Oregon Trail

What amazed us as we rode the wagon across the countryside was how hilly it was. The tall prairie grass makes it look flat and smooth from a distance. Up close, it is a bone-jarring bumpy ride that constantly seems to be rising and falling.

At camp, we joined the tour for dinner. We enjoyed steaks grilled over a campfire, baked potatoes, rolls, green beans and bacon, and cherry cobbler baked in a Dutch Oven. As they retreated to their Tee Pees after dark, we went to our RV, which we had driven out to the prairie campsite.

Over coffee that morning, before the guests left their sleeping bags in their Tee Pees, Carter told me he was looking for help in running his expeditions. He thought a workcamping RV couple would be perfect to help drive the wagons, care for the horses and prepare the meals. He has full hookups on his property. I promised to put the word out, which I did after the trip. But he may still be looking for a couple if you're interested.

Add Retracing Lewis and Clark and the Oregon Trail to Your RV Bucket List

The trip was one of the most interesting and enjoyable things we’ve ever done.

The prairie is beautiful, even when dark clouds bearing lightning and a sudden downpour swept down over the mountains. It has a vastness about it, like the ocean, spreading out wide and full beneath a big sky that bottoms out against a range of low lying mountains. Antelope bound over the little grass hills, eagles float overhead.

I’d highly recommend the modern-day excursions though you need to be in halfway decent shape without back or neck problems. Those wagons are pretty bouncy and riding a horse for extended periods of time does require a basic level of physical health.

If retracing Lewis and Clark and the Oregon trail sounds exciting to you, contact the National Parks Service and ask for their historic trail guides. They have excellent auto touring route maps and booklets that will take you along the same routes the pioneers traveled.

Wagons Ho!

Leave a Reply