Of all the with all the travel we’ve done the past four years, what has impressed us the most are parts of two historic routes: The Lewis and Clark Expedition and the Oregon Trail.

It’s hard to over emphasize the importance of these two 19th century routes. Lewis and Clark discovered the overland route to the Pacific, thus opening up the nation to east-west travel in the days immediately after the Louisiana Purchase. It was a trip that in its day, was as monumental as the American landing on the moon is to ours.

The Oregon Trail pioneers came four decades or so later in their prairie schooners – so named because their wagons were covered with white canvas that made them resemble a ship at sea. Others took routes that sprang off the Oregon Trail on paths called the California Trail and the Mormon Trail as the headed to the Gold Rush and Sat lake City.

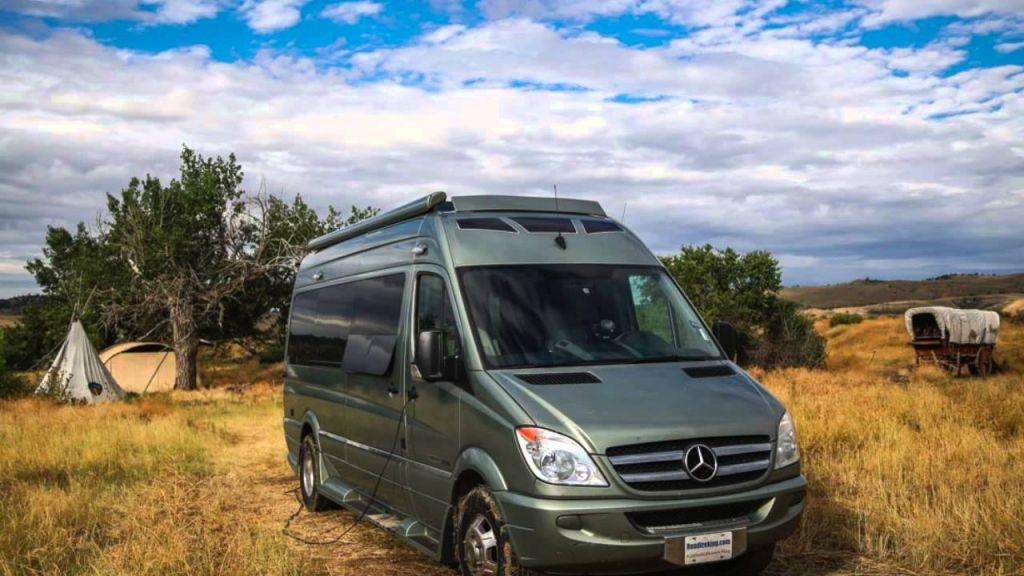

Retracing those routes in our Roadtrek Class B motorhome – the modern equivalent of a covered wagon – was a stimulating journey.

It all started with the wide Missouri. At 2,341 miles, the Missouri River is the longest river in North America. It is impressive to behold. But what you see today is much less than 19th century explorers and pioneers encountered. We have messed it up through channelization and dam building, greatly changing the Missouri River. Today, 67 percent of the Missouri is either channelized for navigation (650) miles or impounded by dams (903 miles). Most of the remaining free-flowing portions of the river are near the headwaters in Montana. Channelization has resulted in the lower river being about 50 percent narrower.

But like I said, it is still impressive. But realizing that it was bigger and wider and wilder 200 years ago makes you wonder how these early explorers did it.

Nicknamed the “Big Muddy,” the Missouri River has long been one of North America’s most important travel routes. Every bend in the river is saturated in history. Her waters saw the canoes of many American Indian tribes, fur trappers, explorers and pioneers. The river served as the main route to the northwest for Lewis and Clark and later became the primary pathway for the nation’s western expansion. The Missouri has witnessed the rise and fall of the steamboat era and given birth to countless communities that settled near her banks.

We started our tour in St. Louis, where the Missouri dumps into the Mississippi at a place called Confluence Point. Standing at the point where the nation’s mightiest two rivers merge, it’s hard not to think of all the dreams, all the hopes and aspirations that welled up in the hearts of those who came this way in the 1800′s. Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery took the Ohio River to the Mississippi, then the Mississippi to the Missouri, beginning their official expedition of the west from this very spot in May of 1804.

As we moved west, we picked up the Oregon Trail. The Oregon Trail, and the ancillary trails that led from it, constituted the single greatest migration in America – as many as a half a million men, women and children who traveled by wagon and by foot west for two decades in the mid-19th Century.

There are lots of books on the trail, museums and monuments throughout the west. In the original migration, most people walked, making it easier on the animals. “Some walked the entire way,” Morris Carter, a Casper, WY outfitter who takes folks on guided tours of the trail told me. “Many were barefoot.”

The biggest danger was accidents. Falls off wagons, under wagons, being tramped or kicked by a horse, snakebite. Disease was widespread, especially cholera. There was a saying the pioneers had about the thousands who died from the virulent intestinal disease: “Healthy at breakfast, in the grave by noon.”

Indeed, as Jennifer and I visited various spots along the Oregon Trail from Missouri westward, we saw several grave sites of pioneers who died along the trail of the disease.

There were also Indian attacks. One wagon train was wiped out just a couple of miles from the route we traveled with arter, just west of Casper. That same band of Indians also killed an entire cavalry platoon sent out to protect the ill-fated wagon train.

What amazed us as we rode Carter's wagon across the countryside was how hilly it was. The tall prairie grass makes it look flat and smooth from a distance. Up close, it is a bone-jarring bumpy ride that constantly seems to be rising and falling.

At camp, we joined the tour for dinner, steaks grilled over a campfire, baked potatoes, rolls, green beans and bacon, and cherry cobbler baked in a Dutch Oven. As they retreated to their Tee Pees after dark, we went to our Roadtrek, which we had driven out to the prairie campsite

The trip was one of the most interesting and enjoyable things we’ve ever done. The prairie is beautiful, even when dark clouds bearing lightning and a sudden downpour swept down over the mountains. It has a vastness about it, like the ocean, spreading out wide and full beneath a big sky that bottoms out against a range of low lying mountains. Antelope bound over the little grass hills, eagles float overhead.

If you’d like to retrace those trails, contact the National Parks Service and ask for their historic trail guides. They have excellent auto touring route maps and booklets that will take you along the same routes the pioneers traveled.

Here’s one for the Oregon Trail – https://www.nps.gov/oreg/index.htm

Here’s one for the Leis and Clark Trail – https://www.nps.gov/lecl/index.htm

Wagons Ho!

Comments are closed.